The Best of Me: An Interview with Heather Landsman

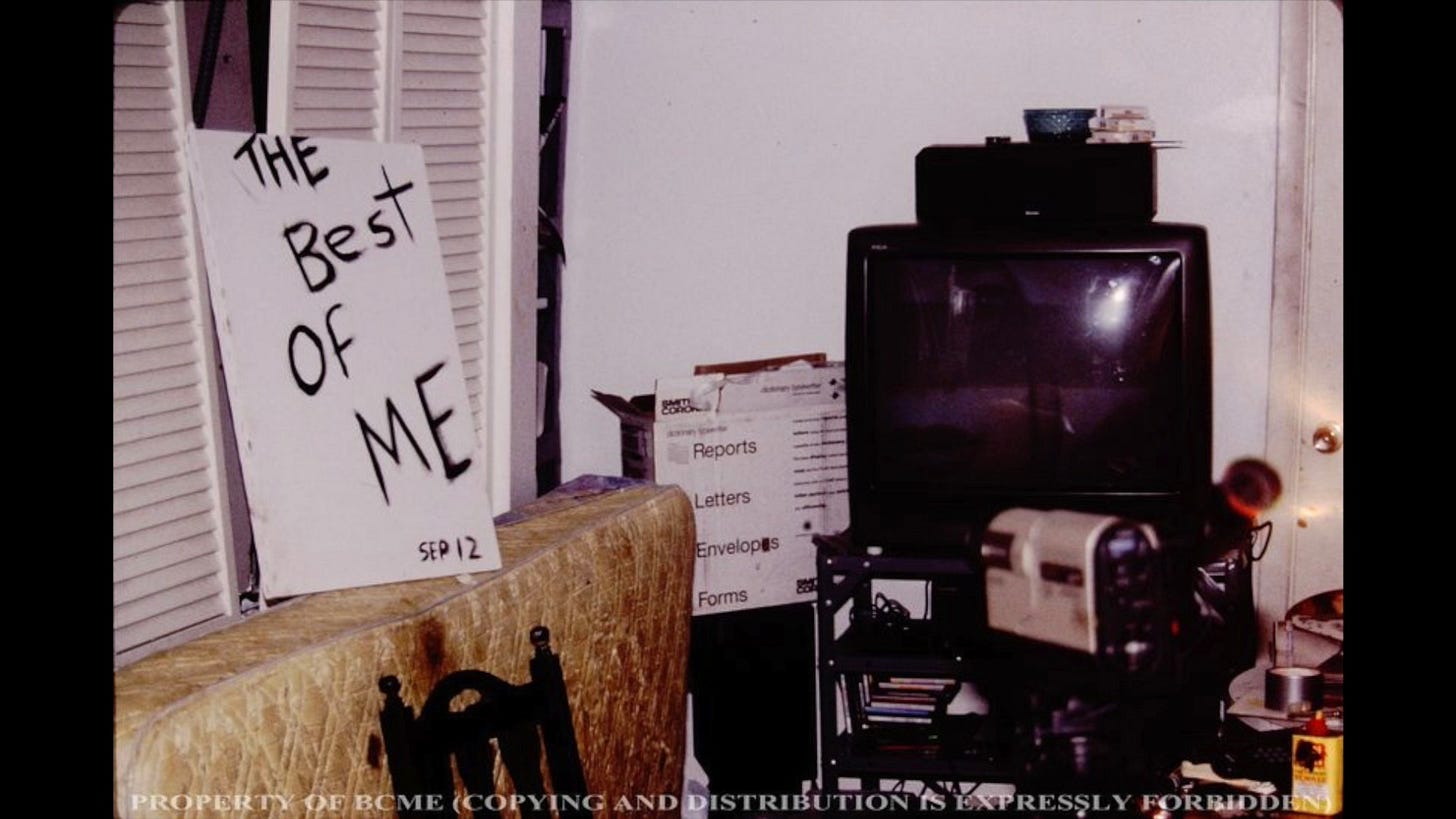

An interview with Heather Landsman, discussing her new archival documentary, The Best of Me. Comprised of the personal video diary entries of Ricardo Lopez, The Best of Me chronicles his final months, weeks, days as he constructs and mails a bomb to Icelandic singer Björk. In 1993, Lopez’s all-consuming fixation began. In 1996, he turns the camera on to explain why she must die by his hand and how.

Olivia Hunter Willke: How did you come across this story?

Heather Landsman: I discovered this story just as a fan of Björk. I’ve been a fan of Björk for a long time. Like, I think, my first real exposure to Björk—I’ve been saying this a lot when people ask me—I think my first real exposure to Björk was Zack Snyder’s Suckerpunch (2011). I forget when that came out, but I was a little kid at the time, and I dragged my mom to see it because I really wanted to see it. And the scene with Emily Browning fighting the giant samurai boss set to Björk’s Army of Me rewired my brain, and I was like, “Okay, where did this song come from?” And that kind of led down the rabbit hole of me becoming a lifelong fan of Björk. But this story, this case, this person, however you want to identify it as, I think I discovered it in, like, middle school. It was after I had watched the movie Perfect Blue (1997) for the first time. Another movie that is one of my all-time favorites, just a perfect movie in my eyes, it’s had such an impact on me as an artist. But, I remember watching that for the first time and then obviously being like a middle school film fan, started going down an internet rabbit hole looking up stuff about it, like, “ending explained blah blah blah” and that eventually led me to discovering, I guess this mass old wives tale internet myth. A conspiracy theory that started and kind of gained traction of people being like “yeah, around the time that they were...” —well this was true—around the time that they were making Perfect Blue, this case happened. And so this myth spread, “Around the time that they were filming, this occurred, and they had to stop production because it freaked Satoshi Kon out.” And you know, that’s not true, he probably did not give a shit about it or had no idea. But it was through that that I discovered it and then obviously went down the further rabbit hole of like, finding footage of the tapes and learning about it and just the way that story, specifically the final tapes of him in the red and green makeup was mythologized by the internet, that image, and also him killing himself on camera. And that really just left a huge impression on me. For a while, it gave me nightmares for just nights upon nights. That was my first real exposure, and it’s a fascination that just hasn’t gone away.

OHW: So, did you see the footage of him committing suicide while you were in middle school?

HL: Yeah, there are a lot of things that I feel like I’ve definitely seen at way too young of an age. Not like... No matter how old you are, you don’t need to be seeing that. My parents were pretty lenient with how much I used the family computer and my exposure to the internet. So, I was either like playing crazy flash games or looking up the craziest shit on Youtube and stuff and leading down a rabbit hole. But yeah, it left a major impression on me, obviously.

OHW: Yeah, it’s interesting. We’re around the same age, I imagine, so like, growing up, my parents didn’t know how far the internet went, and I, we grew up in the time of like LiveLeak and stuff like that. So very, a lot of exposure to heinous, insane visual stuff.

HL: Yeah, LiveLeak. I feel like I ended up on there at one point or another, and I was like, “Whoaaa, no no.” It just scared me, just like the brief minute or so of being on there. I was like, “Oh no, I should not, I gotta get off here! This is gonna freak me out!” But yeah, it really, it kind of doesn’t exist as much anymore. I mean, there’s still like social media and stuff, but it’s so relegated. I mean, it’s still super, at the same time, unrelegated, it’s like a shitshow, but the swiftness to which stuff like that gets wiped now is crazy. As opposed to like 90s, early 2000s, it was just anything, you could just find anything.

OHW: As far as the footage goes, it seems to me much more than a document than a terrorist plot, it seems like the process of planning a suicide, more so. Did you go into this expecting more of a devious mind, more malicious intent? Were you surprised to find someone who was just kind of looking for an excuse to escape?

HL: So going into it, making it was almost just coping with how much it freaked me out. Finding a way to come to terms with it and come at it from a place of deeper understanding of the subject rather than this freaky image of this like guy who blows his brains out. Going into it, I was just like, I’m just ready to see what I learn from this. And yeah, just watching the footage it really brought me into the mind, the very contradictory mind of someone who is clearly... both there’s this plot and then there’s also his personal life and just many different aspects that were brought to light from just watching the footage that I didn’t really know mych about prior. Outside of just the footage, the real knowledge of him, there was a lot of people theorizing and trying to diagnose the “why” of it all. Like, “he did it because of this, he did it cuz of that!” And watching through it all and editing it into a feature really brought to light just everything about him as a person and his life. And, in relation to this, also the brief kind of mentions of and glimpses of his life outside of this whole situation. It was incredibly eye-opening.

OHW: I guess, like, as a viewer. Like youre saying people try and diagnose him, I also had that impulse to go “oh well, he’s bipolar and schizoaffective” or “well, if he had these resources this could’ve been avoided.” As someone constructing this, did you have the urge to interject and theorize? Did this ever come into a form where you were thinking about maybe interviewing people, or was it always strictly, did you strictly want to do just an archival documentary?

HL: From the get-go, I knew that I wanted it to just be just this footage. From his words and it’s presented to an audience, like here it is, take what you will from it. That was very much from the beginning what I knew I wanted to do and what I wanted to make. The editing process was very, it was like 20+ hours of footage, so it was very emotionally and mentally exhausting after a while. I do like to say, I feel like I kind of blacked out, and then all the sudden I have this feature-length documentary made. I was against the idea of editorializing in any way. One huge influence for me, a movie that I really look to that I find, you know, while it is very different, it’s a narrative movie, but even then, the act of making a documentary of any kind is kind of narrativizing in a sense. A big influence for me was Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003). Just because I feel like it covered somewhat similar territory and also one of the things that really stuck with me over the years about that movie—and why its become like one of my favorite movies ever—is how it’s able to project, portray such a horrific act of violence so objectively and if you read, or watch, or listen to any interviews with Gus Van Sant talking about the movie he kind of says the same thing of like, “I very much wanted to present it from every single perspective, as is, objectively, no diagnosing, just showing every single possible thing that could’ve led to this without concluding ‘oh, it was because of this.’” And making the audience come to their own terms with it. That was a really big formal, but also ethical, influence for me. Just because I remember, that’s another movie that I feel like I discovered at a young age, especially in the fedupmovies.com era of just watching movies on the internet. And with that movie, going into it, you know it’s going to be a school shooting movie, and that is really terrifying and freaky to hear. Especially to someone who is in that age group, with the rise of school shootings and coming out of it being like, “Wow, that was a very smart, empathetic, objective, tasteful way to approach that kind of subject and that kind of historical act of violence.” Because you hear that, and you think, “Oh, this is going to be really tone-deaf, really hard to watch for all the wrong reasons.” But, it’s something that has always left an impact on me just for how objective it was and how it doesn’t diagnose. So I knew that was something from the get-go that I wanted to do with this. Just presenting everything in a very objective lens, showing it straight from the source how it was.

OHW: Love that answer. I have an Elephant poster on my wall literally right there, so...

HL: It sounds very morbid to say, but a very rewatchable movie for me.

OHW: It is! No, definitely. So, especially rewatching this, the film starts almost with a sense of levity and grows darker as the reality of the situation he’s constructing sets in. Was this tone apparent from the get-go? Was this intentional or organic? Did it just kind of unfold as is?

HL: The kind of tone of it, I feel like I didn’t really get a sense of what the tone of this was until people started watching it, and started sending it to people to watch, and also started having screenings of it. Kind of while making it, it very much was just a natural, “this was next, and then this was next, and this was next.” And because also there was so much footage, I kind of lost a sense of what the tone was because I was just very focused on, “Okay, this is what important information comes next, or at this point, he contradicts himself after saying the exact opposite thing.” So, I never had a true sense of it while making it, but then... It was really when it first screened at Spectacle and there were people laughing during it at points and I was in shock and like surprised, but not in a like, “Oh, I can’t believe people are laughing at this!” Like there are, I’ve had many cases where I’ve gone to screenings of movies and people laugh at moments where I’m just like, “That is just so despicable that you’re laughing at a moment like this!” But, it wasn’t like that, it was like “Oh wow!” When you edit together a guy saying something and then immediately cut to him contradicting himself after, you’re really just constructing, you’re mathematically constructing the setup and punchline of a joke. And I didn’t realize at the time while making it, seeing it in a packed house, I was like, “Oh yeah, I kind of did make a bleak comedy at that point.” It was something that I never I didn’t have a real sense of while making it just because I was so focused on the “ok, this what needs to come next in the footage.”

OHW: Was this your first time working with archival footage? Had you ever done anything else like this?

HL: Prior to this, I had made some shorts in college. And before this, I was very much making stuff in the realm of like genre pastiche, 70s horror, like riffing on 70s horror. And I’m very grateful for those movies and how they turned out and also the experience of making them. Those were the first real movies I truly wrote, and directed, and produced. I feel like genre pastiche is a great way to learn the form of filmmaking, learning how to properly shoot and cut a movie well. But then, by the time, after I had finished those, my senior thesis film, it was pretty much finished and I was submitting it to festivals, didn’t get into anything. And around this time, it was also my last semester of college, and I was in LA for my last semester. It was kind of a very isolating time being there. I like being in LA in short bursts, but I can not live there. It was during that time that I decided to make this. I was already, with my senior thesis film, kind of starting to dip into some stuff with like contrasting form. The film was mainly shot on 16mm, but there was also some stuff where we did shot-on-VHS stuff, shoot it in front of a CRT kind of deal. And I knew that, with all my ideas moving forward, it’s just been meaning leaning farther away from pastiche and further into that kind of video fuckery and archival experimentation. I was fascinated by this subject, and I was thinking how to approach it. I knew I wanted to approach it for some kind of project. At first, I was thinking maybe some kind of narrative film that takes cues from it, is an original story but... And then I was like, no, I feel like the only way to really properly approach this kind of story, especially while at the same time realizing that all 20 hours of it are on the Internet Archive. I started looking back and seeing if it had really been done before, and prior to this it was just—there was one documentary made a little bit after the case happened. I think it was early 2000s. I watched it. It barely shows any of the tapes, and the whole thing, there’s narration over the whole thing, you barely hear his own voice. I was like, “I feel like this is kind of a tasteless way to go about it.” I was like, “Okay, there’s all this footage, enough to make it into a feature.” And clearly, from doing the research and deep-diving to see if there had been anything done already, like there hadn’t. No one had tried. So I was like, “I might as well give this a shot.” I hadn’t done a movie like this before, and I hadn’t done a documentary, and I feel like it’s something I can really be able to learn from, in a myriad of ways, just making a movie and also the subject itself, and ethically too. It was a huge learning experience for me, the editing process, and just making a documentary for the first time. It was a challenge I knew I wanted to take.

OHW: I know you said going through the footage, you say you kind of blacked out and then you had a movie, but was there a routine? Like, “Okay, I’m gonna get my cup of coffee, I’m gonna sit down, I’m gonna watch this amount of footage.” What was that like? What was the process?

HL: So, it took, I would say, a couple weeks to edit this all together. I literally finished it in like a couple weeks. And that really entailed watching through either one or two tapes a day. Because on the Internet Archive, it was split up into 20 of them, and they’re each an hour long. So, I was like, I’m gonna watch one or two a day. Basically, I’m watching a movie a day or an episode of television a day. And there were also lots of parts where some of the tapes were kind of useless to use. One of them, I only used a piece of, he’s talking and it’s super scratchy and it’s a really dinged up tape. That’s because that’s how it actually was, that’s the only real record of it, is it was a really degraded tape. Then there’s other tapes where it’s just like, he doesn’t really talk or is even on camera. And it’s just either footage of his workbench table or him reiterating points or getting into the intricacies of how to build a bomb with no real commentary or further window into like him as a person or his state of mind. For stuff like that, I admittedly would a little bit of watching at like 1.5x speed just because it was so much to deal with. It was a grueling process to get through, but very much a... I kind of locked myself in my room for a few weeks and came out the end with this completed doc.

OHW: Did anything in the footage particularly surprise you? Was there a moment where you were like, “Oh wow, I didn’t expect that from him or to be in this document?”

HL: I think the most affecting to watch, it really left an impact on me emotionally, was the one where he talks about his condition, the XXY condition. Partially because of that but mostly because it really also gets into his family life and just hearing about, you know, like his relationship with his mother and then, also his siblings, how he’s the youngest sibling. That was really affecting to hear and kind of, like freaky to hear also because I—to give you further context—I have one older brother, and he’s 9 years older than me. So hearing that, that kind of same gap between siblings... It seemed like his family cared about him, but hearing about that kind of sibling/parent dynamic was very striking, and I was like, “Whoa, this is like, really eerie to hear about.” And also, in that tape, he quotes Michael Mann’s Heat (1995), and I was just like “Okay, this is so crazy random, this needs to go in there!” That needs to be in there. That was one that really struck me a lot. And also, another one, just for a different reason, just because of how like, really one of those “what?” moments was the last tape before he takes that long break, and his reasoning being like “You know, maybe I shouldn’t be racist because I watched a multiracial gangbang porn video.” And the fact that made him go, “Maybe I shouldn’t do this!” I was just like, “Wow, that is wild.” Those are the two tapes that really stuck out to me the most while combing through all the footage.

OHW: Was there anything you wanted to include but just couldn’t fit it in, it didn’t meld together? Was there anything you felt pained to leave out?

HL: I can’t say anything really. Again, a lot of the stuff—anything that was cut out was just dead air, or extraneous details, or just reiterating points. I can’t say there’s anything that I was like, “Ugh, this needs to be in there.” I made sure, I believe every single time he’s listening to music is in there, every time you hear a song playing in the background is in there. I don’t think that there’s anything that I was like, “Ugh! I wish I could figure out a way to get that in there!” I wanted, ya know, people to really feel this length of time, of his plan, to really feel the 9 months. Especially in regards to that tape during his break, the one where he’s trying to pose. Also, the end, in the moments leading up to him killing himself, is just the full tape unbroken. Just to see the full wide range of emotions and also to feel the amount of time you’ve been sitting with this footage. But I feel like those were really the key moments where I was able to do that, and outside of that, it felt a little bit extraneous.

OHW: What do you feel is the necessity of this document? Is it for pop culture reference, is it for historical relevance? What do you feel is the importance of compiling this and putting this out into the world?

HL: Going into it, it was very much like a piece of internet horror that freaked me out as a kid and I wanted to tap into that. But, by the end of it, and even from the beginning, when I first started, it made me realize there really hasn’t been... It made me think a lot of the way it got mythologized on the internet and became this kind of source of like, shock horror on the internet. People would just send their friends the clip of him killing himself or him in that green and red facepaint to freak their friends out. It really made me reckon with that and think about that. There hasn’t been much, there hasn’t been really any documentation of this case outside of that. And seeing the full picture, I feel like, at least for me, I see it in a completely different light now. It used to be it would just freak me out and give me nightmares, but now I just see it in a much more sad light. I feel like that’s something that is important just in terms of it being seen is finally having a proper, the fullest documentation possible of this that gives a full picture outside of just like “Oh, this creepy guy like killed himself on camera for Björk! Check out the footage!” By the end of it, that was the important part for me, having a bigger picture that I felt hadn’t really been there.

OHW: Last question, what’s your favorite Björk track?

HL: That’s a good question. I feel like it switches up depending on mood. Recently though, I feel like it’s been Big Time Sensuality. That’s my go-to Björk song when I’m just like walking around or out and about and I just need to lock in. That’s a good one. Army of Me, that’s just the classic, that’s the one that got me into her. I really love all of the stuff on Vespertine (2001). There’s so much, it’s just endless how much music of hers I love. Lately, the one I’ve been listening to a lot on loop has been Big Time Sensuality.

You can keep up with Heather and her work at https://heatherlandsman.com.